|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

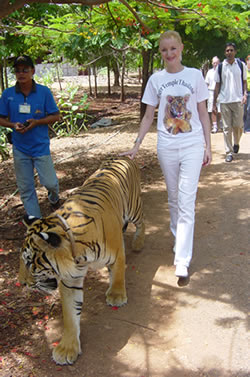

The Cat Whisperer of Thailand "Come on, come over here," commands the bespectacled monk. In the crook of one saffron-draped arm, he’s balancing a knotty stick. In the other rests the enormous head of a fully grown tiger, purring like a kitten. Noting my hesitation, the monk pats the rock on which he and the tiger are perched, and calls me again. With my heart doing a little jig in my throat, I totter over. The monk puts some milk tablets into my shaking hand. "Go on, feed him," he says. I put my hand up to the tiger’s mouth. Purring even louder, like someone just started a lawnmower inside its cavernous, bar coded chest; the big cat starts to lick at the tablets.

It’s a singularly strange feeling to place one’s hand within a whisker (literally) of jaws that could crush you to pulp in an instant; to experience the delicate rasp of a sandpaper tongue designed to obliterate meat from bone; to touch paws the size of two human hands, concealing claws capable of slicing flesh into ribbons with a single swipe. It’s even more so when the tiger is completely unfettered and five of its feline friends are prowling and growling nearby. Call it an accident waiting to happen. Or call it a twisted Thai take on Born Free. One thing you can’t call the Tiger Temple of Kanchanaburi is ordinary. For here Abbot Pra Phusit Khantitaro and his fellow forest monks are engaged in a labor of love, raising abandoned tiger cubs with the aim of one day releasing them " or at least, their offspring " back into the wild. Watpa Luangtabua Yannasampanno, as the temple is properly known, sits atop a rise with commanding views of lush forest. Bangkok is close by and the Burmese border lies just beyond a steep mountain range. This is the front line of Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra’s "war on drugs": heavily armed methamphetamine smugglers haunt lonely hills, tracked by trigger happy border police and army patrols. It’s also a happy hunting ground for poachers, who scour the hills for deer, boar, and other game. Although with an estimated 200 or fewer Indochinese left in Thailand, living mostly along its western border, a tiger is a bonanza, with its paws and penis fetching ludicrous sums from the Chinese "medicine" trade. The big cats have been hunted to the point of extinction. Every day around 4 p.m., Pra Phusit, who prefers to be known as Luangta Chan, oversees the release of the tigers from the cages. The monks then walk them on leashes down a narrow path onto a steep-sided canyon for their daily exercise. A steady trickle of sweaty palmed tourists makes their way to the temple each day to pose with the tigers. It seems an enterprise fraught with peril. None of the monks, Luangta Chan included, has any former training in handling wild animals. But the old abbot seems supremely confident in his mastery over the beasts, yanking on their tails, shouting commands and whispering entreaties like some Buddhist version of Dr. Doolittle, and occasionally administering a sharp prod with his stick.

A big sign at the entrance warns tourists that the temple is not responsible for their safety. And while most of the time the cats appear lazy, content to loll about, roll on their claws or on old truck tires, on several occasions during the two hours we have been in the canyon, it seems like the monk’s control over the animals hangs by a frayed threat. While I am patting Phayu ("Storm") under the abbot’s supervision, behind me, Saifa ("Lightning") is up to no good, aiming half serious swats at his handler. "Saifa, enough!" roars the abbot, spinning around and leaping off his perch with a fluid grace that belies his 58 years. The cat flattens its ears and bares its scimitar fangs, and for a horrible, moment, it seems about to charge. I’m riveted to the rock, feeling puny and helpless. Another monk trots over and they wrestle the tiger to one of several chains staked into the dry red earth, securing it by its collar. The monks also carry bottles of water, which they squirt at the animals whenever they get feisty. If it’s advisable to catch a tiger by the tail, no one ever told these fellows. Luangta Chan founded the temple in 1994, intending it to be a forest retreat where monks could meditate undisturbed. But the local wildlife had other ideas. Soon after the temple was opened, a villager approached the abbot with a one-eyed, one-legged wild rooster, saying he didn’t want to eat the bird, so would the monk care for it? "I took the fowl in. Little did I know, it must have been a leader in the wild chicken community," chuckles Luangta Chan. "Within days, we had dozens of chickens living here. Soon after, a cow arrived; it had been speared by a hunter in its hindquarters. And then a wild boar with a broken back dragged itself here and we nursed it back to health."

The temple soon gained fame locally as an animal sanctuary. One farmer, fallen upon hard times, abandoned his entire herd of livestock here. Now, the 70-hectare property is home to more than 2,000 animals, including pigs, horses, deer, goats, antelopes, peafowl, and gibbons. But the tigers, naturally, are the stars. In February, 1999, poachers killed a mother tiger that had been attacking local livestock near the border with Myanmar. "They had tried to kill and stuff her baby, and had injected it with formalin and made incisions in its stomach. But they botched the job and so they brought the cub here," the abbot says. "I nursed it back to health, and named her Phayu. She was best friends with a dog and all the monks adored her. But she became ill and died at seven months of age." He says he had become attached to the young tiger, and was heartbroken when she died. Then, just weeks later, two healthy male cubs were brought to the temple. "I named one Phayu, in honor of the cub who died, and the other Saifa," he says. As the temple’s fame grew, local villagers and border police brought other abandoned or orphaned cubs. Now, the temple’s tiger population stands at 12, including four cubs that have been born in captivity. Adult Indochinese tigers can weigh close to 200 kilograms, and keeping them fed costs the abbot a fortune. "We feed them dog food," he says. "We rely on donations " every day we spend around 5,000 baht (US$ 120) on food." The temple is also seeking funds for construction of a proper tiger sanctuary. Work has begun for building a series of moat encircled islands upon which the tigers will eventually live. "We need another 20 million baht to complete the first stage," says Luangta Chan. If enough funds can be raised, he also wants to build a restaurant, viewing platforms for tourists, and a tiger research center. "It probably won’t be possible to get the tigers we have here today back into the wild, as they don’t know how to hunt. But for the next generation it is possible. It’s my dream. Once they have a proper sanctuary, we can teach the young ones to hunt and eventually reintroduce them to the region’s national parks." A booklet published by the temple contains photographs, and articles about the tigers. Given some of the descriptions, I am thankful I didn’t read it before venturing into the canyon. "Phayak ("Tiger") is independent, willful and stubborn, and often tends to resort to violence"; Saifa is "moody, nervy, and unpredictable, and can bite if its keepers let their guard down"; Sairung ("Rainbow") is "a temperamental tigress who does not like anyone to annoy her. When upset she will charge." Phayu, I am relieved to hear, is "the most placid tiger in the group, he is clever, playful, and likes showing off." After the big cats are locked up for the evening, I sit with the abbot on the wide teakwood planks of the open-air temple. He brings out the latest edition of his family " a pair of gorgeous two-month old cubs, Decha ("Fire") and Wayo ("Wind"). Their orange and black stripes are just beginning to show through the fluffy white baby fur, and their eyes are a strange blue grey, not the glittering amber hue of mature tigers. At this age, they are just bow-legged and fumblingly clumsy. They are absolutely adorable, but they are already growing at a staggering rate, and within another month will be too strong to frolic unsupervised. "Make no mistake, they are wild animals. And they are angry animals. You have to know what you are doing," he says. "You should never run, even if they charge you. It’s imperative to stand your ground; otherwise their predatory instinct takes over." But the cats also have their playful side. "Most of them love to roll around like pussycats and have their tummies scratched." Surely though, he must at times feel scared of the great beast? "No, not scared," he says, "I respect them. I love them. If you believe in reincarnation, you must realize that I may have been a reincarnation in a past life, or the tigers could have been my friends or my family." A thunderstorm is looming, and the air is charged with wild electricity. In their cages, the big cats pace and roar. Luangta Chan stands and rearranges his saffron robes. He says he is tired, and that it’s time for him to retire to his room. He hands me a little book. "One of my poems," he says, smiling. "Sometimes the tigers inspire me to write."

Watpa Luangta Bua, Yannasampanno, Spring 2006 |

||||||||